Working with Colin Hines as Finance for the Future, I have published this report this morning:

At the core of this report is a simple suggestion. That suggestion is that in order to restore the NHS to the relative state that it was in when Labour left office in 2010 would now require any government to spend an additional £30 billion a year, which should then grow by at least 4% a year in real terms. Fulfilling the mandate that Finance for the Future has been given by its funders, the Polden Puckham Charitable Foundation, I then go on to explain how this money could be raised.

The report's summary is as follows, but I suggest the whole thing (including the appendices) m right be worth read as there is a lot of explanatory material in there:

Summary

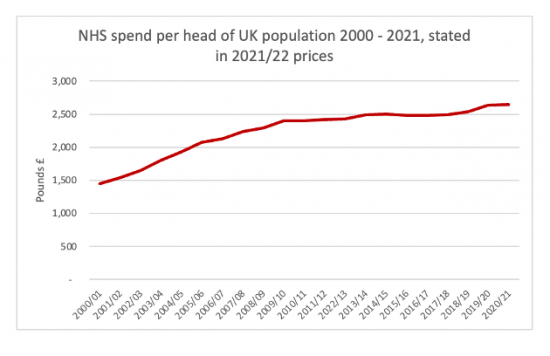

This report looks at the funding of the NHS over time. What it shows, using data on NHS spending from HM Treasury, inflation data from the Office for Budget Responsibility, population data and opinion from the respected healthcare think tank, The Kings Fund, is that it is likely that the NHS is now underfunded by £30 billion a year.

This underfunding is the result of austerity in NHS spending since 2010 when taking into account the demands of an increasing population in the UK and the rising costs of NHS treatments as the range of conditions that the NHS can tackle has grown over time.

The consequence of this underfunding is that at present the NHS should be funded by £3,058 for each person in the country if services supplied were to match the equivalent service level in 2009/10 when the Labour Party was last in office, but actual spending for each person in the UK is about £2,642, meaning that there is a shortfall of more than £400 per person a year in NHS funding in the UK at present.

The trend in spending per person, all stated at 2021/22 price levels, has been as follows:

Spending per person grew rapidly under Labour. It has stagnated since then, at least until the Covid era began.

Actual growth in spending after allowing for population change since 2010 has been less than 0.9% per annum, and ignoring population change 1.56% pe annum.

The King’s Fund has suggested that the last figure should be 4% per annum, apparently taking population change into account in that figure. The Labour Party delivered growth of more than 5% per annum for the first decade of this century. It is the shortfall since then that has cumulatively created the annual shortfall of £30 billion of spending per annum that is likely to exist now.

The question to be asked in that case is how this sum might be funded? Identifying a problem without suggesting a solution helps no one. This report suggests that a range of options are available:

- £10 billion of the funding for this additional cost will arise as a result of the additional taxes paid by those employed by the NHS to deliver the services that are required. These taxes will be paid by those lured back to the service by better working conditions and higher pay, many of whom now work in lower-paid jobs in the private sector, and by those lured back into work having given up on the NHS and work altogether. The impact of the extra NHS spending on growth elsewhere in the economy is also taken into account in this estimate[1].

- At least £5 billion might be raised from taxes paid by those able to return to the workforce either because their own conditions will be sufficiently well managed to allow this or because those that they care for will enjoy better health, letting them return to work.

In that case it is suggested that at least half of the funding required to bring the NHS up to required service levels will be directly generated from the benefits created by that additional spending.

There are, it is suggested, a range of options to meet the remaining £15 billion spending requirement. Three relate to borrowing in various ways:

- A government could simply decide to run a bigger deficit to fund the £15 billion requirement. The impact on the national debt is insignificant, at less than 0.6% of national debt on the basis that the government likes to state it per annum.

- As an alternative, The Bank of England currently has in place a quantitative tightening programme[2] of selling the government debt that it owns that it bought under the quantitative easing programmes that paid for the banking crises of 2008/9, the Brexit crisis of 2016 and the Covid crisis of 2020/21. If £15bn of this programme was cancelled each year and bonds to fund the NHS were sold instead the funding to deliver the healthcare we need could be found. In this case there would be no net impact on the amount of UK national debt owned by third parties.

- If another option is needed, National Savings and Investments could issue NHS Bonds in ISA accounts to provide the funding. £70 billion is saved in ISAs each year. Properly marketed, it would be easy to find £15 billion a year this way.

Alternatively, changes to the tax system that would have no impact on the vast majority of taxpayers could raise the additional funds. These might include:

- Halving the tax reliefs on savings available to the wealthiest 10% of people in the UK each year. At present it is likely that this group enjoy at least £30 billion of pension and ISA tax reliefs each year when they are already wealthy. That subsidy per wealthy person might exceed average Universal Credit payments to each person in receipt of that benefit. Halving this relief would still provide the wealthy with very generous subsidies for their savings but would also leave us with the NHS we all need, the wealthy included.

- Alternatively, since the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons has found that for every £1 spent on tax investigations £18 of additional tax is raised, investing £1 billion in additional funding with HM Revenue & Customs might be enough to recover the funds required for the NHS each year.

- If another option was required, the rate of capital gains tax in the UK is currently set at half the rate of income tax in most cases. This tax is very largely paid by the wealthiest groups in society. If the capital gains tax rate was set at the same rate as the income tax rate then it is possible that the revenue from this tax might double, raising £15 billion a year.

- Other options are also possible, each raising less than £15 billion. For example, another £6 billion a year might be raised by charging an additional 15% income tax on investment income of those below pensionable age who have more than £5,000 of investment income a year since they do not pay national insurance on this but enjoy the benefits of the NHS. And, as the Labour Party has been arguing, the so-called ‘non-dom’ rule that lets wealthy people with an origin outside the UK live here but not pay tax on their overseas income could be abolished, raising maybe £3 billion of tax a year.

It would, of course, be entirely possible to mix and match these options: there is no need for just one source of funding to be used.

What is clear is that to argue that there are no funds for the NHS is wrong: there are multiple options available to fund the NHS that we all need, and the same logic noted here used could also be applied to other essential public services as well.

No political party has an excuse for saying we cannot have excellent public services in that case: we can afford them. All that we need is the political will to deliver them.

[1] This is commonly called the multiplier effect

[2] See the appendix to the report for an explanation of quantitative tightening